libabigail

Our spotlight this week is on libabigail, the ABI Generic Analysis and Instrumentation Library, a C++ library for creating and otherwise interacting with ABI artifacts. What are these artifacts? When you compile code into a binary, the binary basically keeps signatures for types, variables, functions, and variables. All of these together are called an ABI corpus, and we can inspect the corpus for a binary to see if it’s compatible with another library or system of interest, to inspect changes, or even to use them as features for some machine learning oriented approach. I’ve been using and hacking on this library and want to share with you my excitement for the set of tools.

What is libabigail?

The name “libabigail” is an acronym for the “ABI Generic Analysis and Instrumentation Library,” where ABI means “Application Binary Interface.” I heard through a colleague (and I think I read it somewhere) that the library is named after one of the developer’s spouses, which is a pretty great coincidence if you are studying ABI and your spouse happens to be named Abigail (if you can confirm or deny this fact please let us know so we can properly add a reference)! When we compile a binary, there is corpus of metadata in ELF binaries (along with debug information via DWARF) that tells us everything from variables, to types, functions, and declarations for a problem. We call this an ABI corpus.

libabigail can simply let us interact with these corpuses. We can use it like a diff tool to see what has changed between two versions, or otherwise create or manipulate them. For example, if I know the corpus for an ELF shared library along with the corpus of a binary, I can determine if those two things can easily interact.

What does it mean for something to be incompatible?

Let’s say that we inspect a binary with libabigail, and we get a corpus of functions and variable symbols. We then might inspect a different version of the binary and see a change. As an example, let’s say a function’s return type changes. This might mean that the updated version of the library can no longer interact with a shared library on the system. This means that it is incompatible. Libabigail should be able to detect that.

I wanted to quickly get started using libabigail to get a sense of the output and interactions. I was able to use install instructions from sourceforge, API documentation at sourceware, and user documentation to come up with the simple examples below. The scripts I used are provided in the documentation. I decided to only review the core functions that might be useful for my use case.

1. Build a libabigail container

What do you do when you look at a list of dependencies, and are like “Nope!” You build a container, of course! Here is a Dockerfile that I put together to install dependencies and the latest (at the time of writing) release of libabigail:

FROM ubuntu:20.04

ENV DEBIAN_FRONTEND=noninteractive

ARG LIBABIGAIL_VERSION=1.8

RUN apt-get update && apt-get install -y build-essential \

libelf-dev \

autoconf \

libtool \

pkg-config \

libxml2 \

libxml2-dev \

elfutils \

doxygen \

python3-sphinx \

wget \

libdw-dev \

elfutils

RUN ldconfig && \

wget http://mirrors.kernel.org/sourceware/libabigail/libabigail-${LIBABIGAIL_VERSION}.tar.gz && \

tar -xvf libabigail-${LIBABIGAIL_VERSION}.tar.gz && \

cd libabigail-${LIBABIGAIL_VERSION} && \

mkdir build && \

cd build && \

../configure --prefix=/usr/local && \

make all install && \

We then build:

$ docker build -t libabigail .

The build includes the following features (and you can edit the Dockerfile to update or change this):

=====================================================================

Libabigail: 1.8.0

=====================================================================

Here is the configuration of the package:

Prefix : /usr/local

Source code location : ..

C Compiler : gcc

C++ Compiler : g++

GCC visibility attribute supported : yes

Python : python3

OPTIONAL FEATURES:

Enable zip archives : no

Use a C++-11 compiler : no

libdw has the dwarf_getalt function : yes

Enable rpm support in abipkgdiff : no

Enable rpm 4.15 support in abipkgdiff tests : auto

Enable deb support in abipkgdiff : yes

Enable GNU tar archive support in abipkgdiff : yes

Enable bash completion : no

Enable fedabipkgdiff : no

Enable python 3 : yes

Enable running tests under Valgrind : no

Enable build with -fsanitize=address : no

Enable build with -fsanitize=memory : no

Enable build with -fsanitize=thread : no

Enable build with -fsanitize=undefined : no

Generate html apidoc : yes

Generate html manual : yes

The version of libabigail used is 1.8, if you want to change it, define it as a --build-arg:

$ export LIBABIGAIL_VERSION=1.7

$ docker build --build-arg LIBABIGAIL_VERSION -t libabigail .

2. Shell inside

I always get really excited after a container finishes building and I essentially get to shell into another universe. You can then get an interactive terminal as follows:

# run the interactive (i) terminal (t) and remove the container after we exit (rm)

$ docker run -it --rm libabigail bash

Where are the libabigail tools installed? Oh, we haven’t talked about this yet, but libabigail exposes a bunch of different command line tools, each with a specific purpose. Can you guess what “abidiff” is intended for?

$ which abidiff

/usr/local/bin/abidiff

There are a few files for system or user preferences but they are out of scope for this small tutorial. Let’s jump into the tools I’m looking at!

3. abidiff

Abidiff is really similar to the traditional linux diff. Instead of two text files, we are going to be comparing the ABI of two shared libraries in ELF format. One important thing to note (from the documentation) is that:

For a comprehensive ABI change report that includes changes about function and variable sub-types, the two input shared libraries must be accompanied with their debug information in DWARF format. Otherwise, only ELF symbols that were added or removed are reported.

So this means that it’s probably important how you compile your libraries. If you don’t include this debug information, you can’t best use this tool.

Examples

Let’s follow the example and quickly create our own two libraries. These examples come directly from here.

# test-v0.cc

// Compile this with:

// g++ -g -Wall -shared -o libtest-v0.so test-v0.cc

struct S0 {

int m0;

};

void foo(S0* /*parameter_name*/) {

// do something with parameter_name.

}

# test-v1.cc

// Compile this with:

// g++ -g -Wall -shared -o libtest-v1.so test-v1.cc

struct type_base {

int inserted;

};

struct S0 : public type_base {

int m0;

};

void foo(S0* /*parameter_name*/) {

// do something with parameter_name.

}

Inside the container, compile the scripts. Here is a Makefile, and you can run it with Make:

all: test-v0.cc test-v1.cc

g++ -g -Wall -shared -o libtest-v1.so test-v1.cc

g++ -g -Wall -shared -o libtest-v0.so test-v0.cc

$ make

We now have two libraries that we can compare with libabigail’s abidiff. Before you run this - take a look at the scripts. What do you expect to see?

$ abidiff libtest-v0.so libtest-v1.so

Functions changes summary: 0 Removed, 1 Changed, 0 Added function

Variables changes summary: 0 Removed, 0 Changed, 0 Added variable

1 function with some indirect sub-type change:

[C] 'function void foo(S0*)' at test-v1.cc:12:1 has some indirect sub-type changes:

parameter 1 of type 'S0*' has sub-type changes:

in pointed to type 'struct S0' at test-v1.cc:8:1:

type size changed from 32 to 64 (in bits)

1 base class insertion:

struct type_base at test-v1.cc:4:1

1 data member change:

'int S0::m0' offset changed from 0 to 32 (in bits) (by +32 bits)

If we had written scripts with functions that changed names (not included here) we would see that too:

$ abidiff libtest-v2.so libtest-v3.so

Functions changes summary: 1 Removed, 0 Changed, 1 Added functions

Variables changes summary: 0 Removed, 0 Changed, 0 Added variable

1 Removed function:

[D] 'function void foo(S0&)' {_Z3fooR2S0}

1 Added function:

[A] 'function void bar(S0&)' {_Z3barR2S0}

This is really neat, and it’s also why it’s so important to consider these kind of changes when you update your software. Binaries are essentially black boxes without these tools. With a tool like libabigail’s abidiff we can quickly see how they changed. I think this is really cool.

4. abipkgdiff

This looks to be similar to abidiff, but it’s used for entire package files (e.g., rpm). I haven’t hit this use case yet, but I imagine if you build rpms (or similar) it would be useful. Here is an example:

$ abipkgdiff --self-check --d1 mesa-libGLU-debuginfo-9.0.1-3.fc33.x86_64.rpm mesa-libGLU-9.0.1-3.fc33.x86_64.rpm

If two packages are equal, the return code is 0. It’s non-zero otherwise. You can find the full examples here

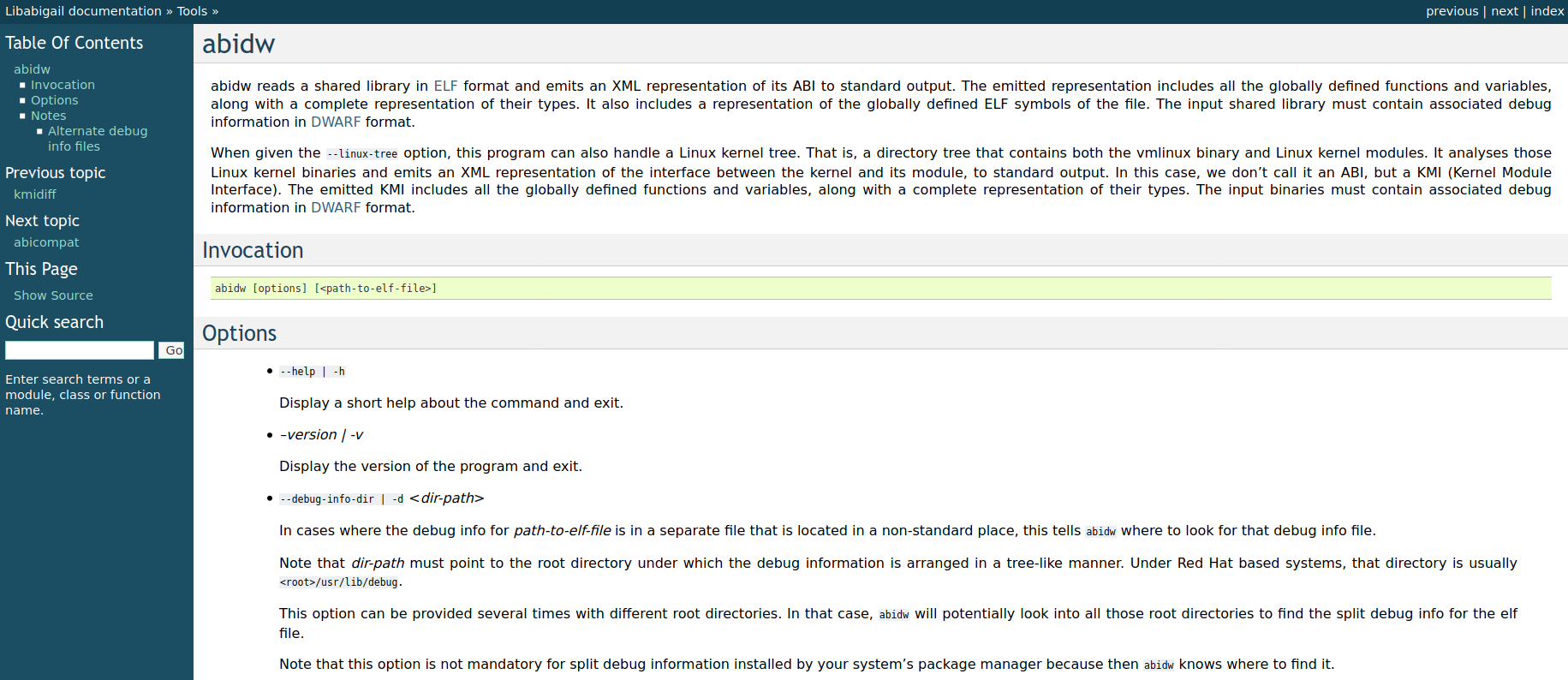

5. abidw

The command line tool abidw I’m excited about, because it reads an entire shared library and outputs an xml representation. It outputs:

- globally defined functions and variables

- a complete representation of their types

- a representation of the globally defined ELF symbols of the file

Notably, the documentation says:

The input shared library must contain associated debug information in DWARF format.

Let’s try running it on one of our binaries:

$ abidw libtest-v0.so

<abi-corpus path='libtest-v0.so' architecture='elf-amd-x86_64'>

<elf-function-symbols>

<elf-symbol name='_Z3fooP2S0' type='func-type' binding='global-binding' visibility='default-visibility' is-defined='yes'/>

</elf-function-symbols>

<abi-instr version='1.0' address-size='64' path='test-v0.cc' comp-dir-path='/example' language='LANG_C_plus_plus'>

<type-decl name='int' size-in-bits='32' id='type-id-1'/>

<type-decl name='void' id='type-id-2'/>

<class-decl name='S0' size-in-bits='32' is-struct='yes' visibility='default' filepath='/example/test-v0.cc' line='4' column='1' id='type-id-3'>

<data-member access='public' layout-offset-in-bits='0'>

<var-decl name='m0' type-id='type-id-1' visibility='default' filepath='/example/test-v0.cc' line='5' column='1'/>

</data-member>

</class-decl>

<pointer-type-def type-id='type-id-3' size-in-bits='64' id='type-id-4'/>

<function-decl name='foo' mangled-name='_Z3fooP2S0' filepath='/example/test-v0.cc' line='8' column='1' visibility='default' binding='global' size-in-bits='64' elf-symbol-id='_Z3fooP2S0'>

<parameter type-id='type-id-4'/>

<return type-id='type-id-2'/>

</function-decl>

</abi-instr>

</abi-corpus>

So neat! The abi corpus is broken into elf-function-symbols and abi-instr (abi instructions) and each has it’s own nesting (maybe we would call these subcorpora). Each definition seems to have paths, sizes, names, and versions. I’d really like to see this in json.

Note that this is a rather small example - I tried running abidw on libabigail.so itself, and the result was something

like 177MB (when I formatted into json). Super chonk! There are a lot of additional flags that might be useful.

$ abidw libtest-v0.so --stats

$ abidw libtest-v0.so --annotate

$ abidw libtest-v0.so --load-all-types

It looks like this tool is also able to generate a similar xml structure but for an abidiff. You can find the full examples here

5. abicompat

abicompat sounds like what you’d expect - “ABI compatibility!” and it’s another useful tool because it allows you to quickly check if an application that links against a shared library is compatible with a different or later version of that same library. I’m interested to see what information is shared if this isn’t the case. For this test, you would want to compile a library with some useful functions:

g++ -g -Wall -shared -o libcompat-0.so test0.cc

and then link the first against some other application.

$ g++ -g -Wall -o test-app -L. -lcompat-0 test-app.cc

In the real world, imagine that you then update your original library. Let’s compile the new one:

$ g++ -g -Wall -shared -o libcompat-1.so test1.cc

Is it going to still work with your application? The tool abicompat can help us to answer

this question!

$ abicompat test-app libcompat-0.so libcompat-1.so

ELF file 'test-app' might not be ABI compatible with 'libtest-1.so' due to differences with 'libtest-0.so' below:

Functions changes summary: 0 Removed, 2 Changed, 0 Added functions

Variables changes summary: 0 Removed, 0 Changed, 0 Added variable

2 functions with some indirect sub-type change:

[C]'function foo* first_func()' has some indirect sub-type changes:

return type changed:

in pointed to type 'struct foo':

size changed from 32 to 64 bits

1 data member insertion:

'char foo::m1', at offset 32 (in bits)

[C]'function void second_func(foo&)' has some indirect sub-type changes:

parameter 0 of type 'foo&' has sub-type changes:

referenced type 'struct foo' changed, as reported earlier

You can find this full example here.

How do I cite it?

I don’t see a direct publication, but I suspect you can cite it directly on sourcware:

The ABI Generic Analysis and Instrumentation Library [Online].

Available from: https://sourceware.org/libabigail

[Accessed: 21 February 2021]

How do I get started?

My “tutorial” above based on the main documentation is fairly limited, but the good news is that most of it comes from this documentation at sourceware.org. Along with the tools that I discussed, there are several others for you to explore! If you want to see the code tree, see https://sourceware.org/git/libabigail.git. Other useful resources might include:

Recent Posts

- Posted on 21 Mar 2021

- Posted on 07 Mar 2021

- Posted on 21 Feb 2021

- Posted on 21 Feb 2021